NDLR de Vigi-Sectes de 2025 :

Ce livre du premier président de l'association Vigi-Sectes, n’est bien entendu plus d’actualité, le vocabulaire est parfois désuet voir archaïque, les données sont depuis belle lurette non valides. Nous reproduisons toutefois ce document sans en garantir aucune véracité, ni en avoir fait de vérification, afin que les chercheurs ou historiens, puissent retrouver un regard du passé sur le panorama des sectes et religions du siècle dernier.

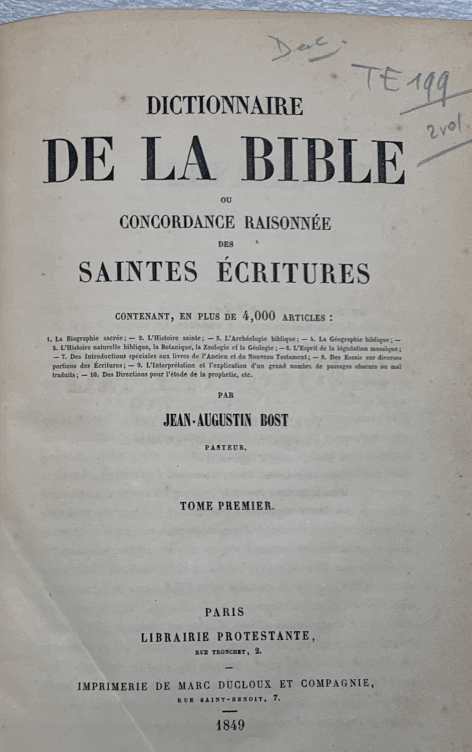

Livre de GÉRARD DAGON : LES SECTES EN FRANCE, 1958

PRÉFACE

« Où est ton frère » Tel était le thème du Rassemblement Protestant d’octobre 1956.

« Mon frère se trouve dans mon Eglise, dans ma paroisse, dans une Eglise-sœur on une Eglise rivale, à la porte de l’Eglise ou au-dehors ! » Telles étaient les réponses à cette question.

Un grand nombre de nos frères se trouve aussi dans de petites communautés qu’avec mépris nous qualifions de sectes.

Ce petit dictionnaire des sectes a pour but de demander aux chrétiens authentiques de prendre conscience de l’existence d’innombrables sectes et d’affermir leur foi évangélique, fondée sur le roc de la Bible, la Bible seule et la Bible entière.

Beaucoup de nos frères nous quittent pour trouver leur bonheur dans des sectes. Pourquoi nous quittent-ils ? Ne sommes-nous pas les premiers responsables ?

G. D.

Les critiques, compléments, modifications, erreurs peuvent être signalés à Gérard DAGON à STRASBOURG-Cronenbourg (B.-Rh.)

BIBLIOGRAPHIE SOMMAIRE

- ALEXANDER H. E., Pentecôtisme ou Christianisme ; Editions do la Maison de la Bible, Paris, 1954.

- ALEXANDER 11. E., Occultisme ou Christianisme ; Editions de la Maison de la Bible, Paris, 1954.

- ALEXANDER H. E., Sabbatisme on Christianisme; Editions de la Maison de la Bible, Paris, 1954.

- AMADOU Robert, L’Occultisme; Editions Juillard, Paris, 1950.

- AMIABLE L., La révérende Loge des Nouf-Sœurs, Paris 1897.

- ARNAL Albert, Le Ministère au point de vue darbyste, Genève 1889.

- BEDARIEUX Pierre, La secte tragique des Témoins du Christ; Editions de l’Arabesque, Paris 1954.

- BERNARDIN Ch., L’Histoire des Francs-Maçons à Nancy, Nancy 1909.

- BERTELOOT J., Lu Franc – Maçonnerie et l’Eglise Catholique, Paris 1947.

- BERTELOOT J., Les Francs-Maçons devant l’Histoire, Paris 1949.

- BERTELOOT J., Jésuite et Franc-Maçon, Paris 1952.

- BILLY A., Chapelles et Sociétés secrètes; Edit. Correa, Paris, 1951.

- BOIS Henri, Le Réveil du Pays de Galles, Toulouse 1905.

- BOIS Jules, Les Petites Religions de Paris; Editions Flammarion.

- BOIS Jules, Le Miracle Moderne; Editions Ollcndorf, 1907.

- BOLL Marcel, L’Occultisme devant la Science ; Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 1951.

- BORD G., La Franc-Maçonnerie en France, Paris 1909.

- BOUCHER J., La symbolique maçonniquo, Edit. Dervy, Paris 1948.

- BOUDOU Pierre, Le Spiritisme et ses dangers; Editions Féret, Bordeaux 1921.

- BOURGUET Pierre, Problèmes de la Mort et de l’Au-Delà; Edit. S. C. E., Paris 1947.

- BOUSQUET G. H., Les Mormons, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 1949.

- BOUTET Frédéric, Les Aventuriers du mystère ; Editions Gallimard, Paris.

- BOUTON A., Histoire de la Franc-Maçonnerie dans la Mayenne, Le Mans 19

- BROADBENT E. H., Le Pèlerinage Douloureux de l’Eglise fidèle, Yverdon, Suisse, 1938.

- BROOKS L. K., Vérité et Erreur ; Editions Vie et Liberté, Lausanne, Suisse, 1955.

- BRUNEL G., Le Buchmanisme, chee l’auteur à Boisset-Anduze, près Toulouse, 1946.

- BYSE Ch., La clé des Saintes Ecritures d’après Swedenborg ; Edit. Fischbacher, Paris.

- BYSE Ch., La Providence d’après Swedenborg; Editions Fisch- bacher, Paris.

- CARINGTON W., La Télépathie; Editions Payot, Paris 1948. CARTON Paul, La science occulte et les sciences occultes, chez l’auteur à Brévannes ; Paris 1935.

- CASTELLAN Yvonne, Le Spiritisme, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris 1954.

- CASTELLAN Yvonne, La Métapsychique, Presses Universitaires de France, 1955.

- CHADOURNE Marc, Quand Dieu se fit Américain; Edit. Fayard, Paris 1950.

- CHERY H. Ch., L’Offensive des Sectes ; Edit, du Cerf, Paris 1954. CHEVRIER Serge, L’Eglise et la Théosophie, 1921.

- CHOBAUT H., Les débuts de la Franc-Maçonnerie à Avignon, Avignon 1924.

- CHOCHOD Louis, Occultisme et magie en Extrême Orient; Edit. Payot, Paris 1949.

- COLINON Maurice, Faux Prophètes et Sectes d’aujourd’hui; Edit. Plon, Paris 1953.

- COLINON Mauricey, L’Eglise ten face dte la Franc-Maçonnerie; Paris 1955.

- COLINON Maurice, Esprit es-tu là ? Edit, du Centurion, Paris 1956. COLINON Maurice, Les Guérisseurs ; Grasset, éditeur à Paris, 1957. COULERU C.-B., Le spiritisme déguisé.

- CRISTIANI L., Brève histoire des Hérésies, Edit. Fayard, Paris 1956. CURCIO Michèle, Le Guide de l’Occultisme ; Ed. Debresse, Paris 1956. CYRILLE R. P., Pourquoi je ne suis pas adventiste?

- Sté. François, Paris 1949.

- DARE Paul, Magie blanche et magie noire aux Indes, Payot, Paris. 1947.

- DEB0UXB1TAY R., Antoine le Guérisseur et l’Antoinisme ; 1934.

- DELANNE Gabriel, Le Spiritisme devant la Science ! Editions Jean Meyer, Paris, 1927.

- DENIS Léon, Spiritisme et Médiumnité ; Editions Jean Meyer, Paris.

- DENIS Léon, Christianisme et Spiritisme ; Edit. Jean Meyer, Paris.

- DENIS Léon, Synthèse doctrinale et pratique du Spiritisme ; Edit. Jean Meyer, Paris.

- DESMETTRE H., Un chrétien devant les Témoins de Jéhovan, Lille, 1949.

- DESMETTRE H., L’Antoinisme, Lille, 1949.

- DOLLINGER, L’Eglise et les Eglises, Touray, 1862.

- DOULIERE Edmond, La doctrine des Témoins de Jéhovah devant la Bible ; Editions Nephtali, Belgique, 1950.

- DUHEM Paul, Contribution à l’étude de la folie chez les spirites, Steinheil, Paris, 1904.

- ENCAUSSE Philippe, Science occulte et déséquilibre mental, Payot, Paris, 1943.

- FELICE Ph. de, Foules en délire, Paris, 1947.

- FINDEL J. G., Histoire de la Franc-Maçonnerie ,Paris, 1866.

- FLOTTE Gaston de, Les sectes protestantes, Paris, 1856.

- FORESTIER R. le, L’Occultisme et la Franc-Maçonnerie écossaire, Paris, 1928.

- GASCOIN E., Les religions inconnues ; Edit. Gallimard, Paris 1928.

- GE ARON Patrick, Le Spiritisme, sa faillite, Lethielleux, 1932.

- GEE Donald, Les Fruits de l’Esprit, Rouen, 1947.

- GENOUY O., Le Darbysme, Genève, 1884.

- GERBER Robert, Le mouvement adventiste, Dammarie-les-Lys, 1950.

- GEYRARD Pierre, Les petites Eglises de Paris ; Editions Emile- Paul, Paris, 1936.

- GEYRAUD Pierre, Les Sociétés secrètes de Paris ; Editions Emile- Paul, Paris, 1937.

- GEYRAUD Pierre, Les Religions nouvelles de Paris ; Editions Emile- Paul, Paris, 1939.

- GEYRAUD Pierre, Sectes et Rites ; Editions Emile-Paul, Paris, 1954.

- GEYRAUD Pierre, L’Occultisme à Paris ; Editions Emile-Paul, Paris, 1953.

- RONY Jérôme-Antoine, La Magie, Presses Universitaires de F rance, Paris, 1956.

- ROTH Henri, Aurorisme ou Christianisme ; Ed. de la Maison de la Bible, Paris, 1954.

- ROURE Lucien, Le merveilleux spirite.

- ROUSSEAU Georges, Le drame anabaptiste, Société des Publications Baptistes, Paris, 1952.

- ROUSSEAU Georges, Histoire des Eglises Baptistes, Société des Publ. Bapt., Paris, 1951.

- RUFFAT A., La superstition à travers les âges; Editions Payot, Paris, 1950.

- SEDIR, Histoire et doctrines des Rose-Croix ; Editions Legrand, Bilhorel, 1932.

- SEGUY Jean, Les sectes protestantes dans la France contemporaine; Editions Beauchesne, Paris, 1956.

- SEROUYA Henri, Le Mysticisme, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris, 1956.

- SIGHELE Scipio, Psychologie des Sectes, Paris, 1898.

- T AXIL L., Les mystères de la Franc-Maçonnerie dévoilés; Editions Letouzey et Ané, Paris.

- THOMAS-BRES A., Le baptême du Saint-Esprit, Nice, 1946.

- TOCQUET Robert, Tout l’occultisme dévoilé; Editions Amiot- Dumont, 1952.

- VAREZE Claude, Allan Kardec ; Editions Athéna.

- VAUCHER Alfred, L’Histoire du Salut, Dammarie-les-Lys, 193#.

- VERRIER Abbé, Faux témoins démasqués, chez l’auteur à Raisinés, Nord, 1954.

- VIOLLET D‘, Le Spiritisme dans ses rapports avec la folie.

- VULIAUD Paul, La Fin du Monde, Paris, 1952.

- WELTER G., Histoire des Sectes chrétiennes, Paris ; Editions Payot, 1950.

- WIRTH O., La Franc-Maçonnerie rendue intelligible à ses adeptes, Paris, 1931.

- WITTEMANS F., Histoire des Rose-Croix; Edit. Adyar, Paris 1925.

- WYSS Paul, Aperçu sur les sectes chrétiennes, Librairie Evangélique, 76, Rue Dansaert, Bruxelles, 1936.

- ZWEIG Stéphan, La Guérison par l’Esprit; Editions Stock, 1934.

INTRODUCTION:

I. Les Sectes

MISE AU POINT : Il ne sera parlé dans cette enquête que des sectes religieuses se rapprochant plus ou moins vaguement du Christianisme ; ne seront donc pas mentionnées les sectes juives, musulmanes, isiaques, bouddhistes ou politiques qui pullulent en France. Cette enquête est forcément incomplète et imparfaite. Les renseignements ont été recueillis dans les documents officiels des sectes, les dires des sectaires et les journaux des différents mouvements.

Pour éviter tout classement erroné, les sectes sont présentées par ordre alphabétique.

REMARQUE : Le mot de secte a pris un sens préjoratif, il suggère l’orgueil et le mépris. Par commodité, il sera employé dans cette enquête dans le sens de «communauté» ou «conventicule», sans aucune nuance péjorative. Le nombre de membres ne permet pas de distinguer une Eglise d’une secte.

ETYMOLOGIE : Le mot de secte vient à la fois du latin secare- couper et du latin sectari-suivre. Une secte se sépare de l’Eglise pour suivre une doctrine nouvelle.

DEFINITION : Une secte est un mouvement religieux hostile à l’Eglise pour lequel toute la Bible n’est pas uniquement et intégralement la Révélation Divine.

ORIGINE DES SECTES : Les sectes naissent le plus souvent à la suite d’une lacune de l’Eglise. Elles sont des «poteaux avertisseurs». Le fondateur de secte croit que tous les hommes avant lui se sont trompés. Personne n’avait l’Esprit de Dieu que lui seul possède. Il a pour mission de partir à zéro pour fonder la véritable communauté des saints.

LES TROIS TYPES DE SECTES :

a) Les sectes qui mutilent la Bible : Elles insistent sur quelques versets en ignorant d’autres. Elles choisissent des points particuliers de l’Ecriture pour fonder leur doctrine.

b) Les sectes qui déséquilibrent la Bible: Elles insistent trop sur certains versets et les exagèrent, elles n’ont pas de vue d’ensemble.

c) Les sectes qui ajoutent à la Bible d’autres livres de doctrine.

CARACTERISTIQUES D’UNE SECTE: La secte prétend être la seule véritable Eglise. Elle est hostile à toutes les Eglises et très anti-œcuménique. Elle groupe uniquement des purs, des sauvés, sans se soucier de théologie et de dogmatique. Le salut vient de la secte qui a seule toute la Vérité. La secte est l’Eglise parfaite tandis que l’Eglise est la Congregatio sanctorum qui attend son Sauveur. La secte ajoute souvent à la Bible des livres de doctrine à valeur égale, elle associe souvent à Jésus-Christ un autre Sauveur. Avec fanatisme la secte aime spéculer sur les chiffres de la Bible. La secte développe le pharisaïsme : cf Luc XVIII, 11 : «Mon Dieu, je te remercie de ce que je ne suis pas comme ces misérables catholiques ou protestants…».

Les assemblées sectaires sont chaudes, on se connait et on s’embrasse.

GENERALITES : Les sectes évoluent constamment : se divisent, s’unissent, disparaissent pour renaître sous un autre nom. Le plus souvent elles font une propagande tapageuse : visites, colportage, porte-à-porte, tracts, meetings, etc… Leurs lieux de culte sont très simples, l’entrée est gratuite, aucune quête n’est faite (il y a des exceptions), la salle est bien chauffée en hiver…

LES SECTES DANS LE NOUVEAU TESTAMENT : Des sectes se forment depuis la naissance du Christianisme. Ce sont les «hairesis» de Actes V, 17 ; XV, 5 ; XXIV, 5 ; XXIV, 14 ; XXVI, 5 ; XXVIII, 22 ; I Corinthiens XI, 18—19 ; Galates V, 20 et II Pierre II, 1. Jésus a prévu les sectes en de nombreux endroits du Nouveau Testament, comme dans Matthieu XXIV, 4—26 et Paul aussi dans Galats I, 6—10.

SECTES ANCIENNES : Le phénomène sectaire du XXe siècle n’est pas étonnant, il est aussi ancien que le Christianisme : Acacia- nisme, adoptianisme, anoméisme, apollinarisme, arianisme, bo- gomilisme, collyridisme, catharisme, donatisme, ébionisme, en-

cratitisme, eutychianisme, gnosticisme, homéisme, homoouséisme,, macédonisme, manichéisme, marcionisme, mélécianisme, mellu- sianisme, millénarisme, modalisme, monarchianisme, monotbé- lisme, montanisme, naassénisme, nestorianisme, novacianisme, origénisme, orphisme, paulicianisme, patripassianisme, pélagianisme, pétrobussianisme, photinisme, pneumatomacisme, priscil- lianisme, quiétisme, sabéllianisme, subordinationisme, spiritualisme, tanchelmisme, etc… sont quelques exemples parmi mille autres.

REMERCIEMENTS : Que soient remerciés ici vivement les dieux, christs, esprits, prophètes, papes, patriarches, curés, évêques, diacres, anges, prêtes, apôtres, etc… des différentes sectes pour leurs précieux renseignements.

II. Les Eglises

Voici une liste des Eglises de France qui ne doivent pas être confondues avec les sectes.

a) EGLISES CATHOLIQUES:

- Eglise Catholique Romaine de France, 10, Avenue du Président- Wilson, Paris 16e.

- Eglise Catholique Romaine Concordataire d’Alsace et de Moselle, 16, Rue Brûlée, Strasbourg.

- Eglise Catholique Apostolique et Gallicane, 96, Bld. Auguste Blanqui, Paris 13e; lObis, Rue des Boulangers, Paris; Aix- en-Provence, Bordeaux, Cannes, Digne, Mios, Pessac, Res- tigné, Toulouse, Tours.

- Eglise Catholique Orthodoxe Occidentale ou Eglise Française de l’Ascension ou Eglise Catholique Evangélique ou Eglise Libre Catholique, 26, Rue d’Alleray, Paris 15e et 72, Rue de Sèvres, Paris ; Rouen.

- Petite Eglise Catholique, Bretagne, Bressuirois, Bugey, Courlay, Fougères, Lyon, Nantes, Roannais.

- Eglise Vieille-Catholique Française, Boîte postale 2.07, Paris V et Boulevard de la Glacière, Paris.

- Eglise des Vieux-Catholiques en France, 9bis, Rue Jean-de- Beauvais, Paris 5°.

- Eglise Vieille-Catholique de France, 5, Rue d’Aquesseau, Paris. Eglise Catholique et Apostolique de France ou Eglise Catholique Mariavite, 9, Rue Perrault à Nantes.

- Eglise Catholique Apostolique et Avignonnaise de France. Eglise Catholique Janséniste de France.

- Eglise Catholique d’Action Française.

- Eglise Catholique Béguine, Rhône, Loire.

- Eglise Catholique Blanche, Ain.

- Eglise Catholique Eutychienne, Paris, Marseille.

- Eglise Catholique Copte, Paris.

- Eglise Catholique Melckite, Rue Saint-Julien-le-Pauvre, Paris. Eglise Russe-Catholique, 39, Rue François-Gérard, Paris.

- Eglise Catholique Arménienne, lObis, Rue Thouin, Paris. Eglise Catholique Syrienne, 15, Rue des Carmes, Paris 5°. Eglise Catholique Maronite, 17, Rue d’Ulm, Paris 5e.

- Eglise Catholique Chaldéenne, 4, Rue Greuze, Paris 16e.

- Eglise Catholique Anglaise, 50, Avenue Hoche, Paris 8°.

- Eglise Catholique AUemande, 89, Rue des Pyrénées, Paris 20°. Eglise Catholique Vietnamienne, 36, Bld. Raspail, Paris V. Eglise Catholique Polonaise, 263bis, Rue St-Honoré, Paris Ier. Eglise Catholique Coréenne, 9, Rue du D’ Roux, Paris 15e. Eglise Catholique Belge-Flamande en France.

- Eglise Catholique Bielorussienne en France.

- Eglise Catholique Espagnole en France.

- Eglise Catholique des Etats-Unis en France.

- Eglise Catholique d’Extrême-Orient en France.

- Eglise Catholique Grecque en France.

- Eglise Catholique Hollandaise en France.

- Eglise Catholique Hongroise en France.

- Eglise Catholique Italienne en France.

- Eglise Catholique Lithuanienne en France.

- Eglise Catholique Luxembourgeoise en France.

- Eglise Catholique Roumaine en France.

- Eglise Catholique Scandinave en France.

- Eglise Catholique Slovaque en France.

- Eglise Catholique Slovène en France.

- Eglise Catholique Suisse en France.

- Eglise Catholique Tchèque en France.

- Eglise Catholique Ukrainienne en France.

b) EGLISES ORTHODOXES:

- Eglise Orthodoxe Russe de France, 12, Rue Daru, Paris 8e; Biarritz, Bordeaux, Cannes, Marseille, Menton, Nice, Strasbourg.

- Eglise Orthodoxe de France, 6, Rue de la Verrerie, Paris 4e; Colombes, Lyon, Montpellier, Nancy, Nice, Rennes.

- Eglise Orthodoxe Arménienne de France, 5, Rue Jean-Goujon, Paris 8“ ; Marseille.

- Eglise Orthodoxe Grecque de France, 5, Rue Georges – Bizet, Paris 16“ ; Marseille.

- Eglise Orthodoxe Grégorienne de France, 43, Rue François- Gérard, Paris 16°.

- Eglise Orthodoxe Roumaine de France, 9bis, Rue Jean-de-Beau- vais, Paris 5“.

- Eglise Orthodoxe Française de Saint-Irénée, 96, Bld. Auguste- Blanqui, Paris 13“.

c) EGLISES PROTESTANTES :

- Eglise Réformée de France, 47, Rue de Clichy, Paris 9e.

- Eglise Réformée Evangélique Indépendante, Place d’Assas, Le Vigan, Gard.

- Eglise Réformée d’Alsace-Lorraine, 2, R. du Bouclier,Strasbourg.

- Eglise Evangélique Luthérienne de France, 16, Rue Chauchat, Paris 9e.

- Eglise Evangélique Luthérienne Libre de France, 105, Rue de l’Abbé-Groult, Paris 15“.

- Eglise Evangélique de la Confession d’Augsbourg d’Alsace- Lorraine, la, Quai Saint-Thomas, Strasbourg.

- Eglise Evangélique Libre de France, Annonay, Ardèche.

- Eglise Evangélique Méthodiste de France, 3, Rue Saint-Dominique, Nîmes.

- Eglise Méthodiste Evangélique de France, 7, Rue Kageneck, Strasbourg.

- Eglise Evangélique Baptiste de France, 48, Rue de Lille, Paris 7“.

- Eglise Baptiste de France, 4, Rue Vespasien, Nîmes.

- Eglise Luthérienne Indépendante, 4, Avenue Charles-Flahaut, Montpellier.

- Eglise Evangélique Arménienne de France, 9, Rue du Dr Re- batel, Lyon.

- Eglise Evangélique de France, Place Benjamin-Zix, Strasbourg.

- Eglise Evangélique Mennonite de France, 22, Rue d’Ingersheim, Colmar.

Les ADVENTISTES

REMARQUE :

Les Adventistes sont divisés en de nombreuses sectes rivales dont les deux principales sont : L’Eglise Adventiste du Septième Jour et l’Eglise Adventiste Réformée. On trouve en France quelques adventistes ne se rattachant pas à ces deux sectes, ils appartiennent aux groupements suivants :

EGLISE CHRETIENNE ADVENTISTE : Elle fut fondée par Storr en 1861. Comme elle sanctifie le dimanche, elle est encore appelée Eglise Adventiste du Premier Jour. Elle enseigne l’immortalité naturelle de l’âme, le sommeil de l’âme après la mort, la destruction de l’âme des impies après le jugement dernier. Elle a 67.000 adeptes dans le monde, presque tous aux Etats-Unis, et moins de dix en France.

UNION DE LA VIE ET DE L’AVENEMENT: Elle est sortie de l’Eglise Adventiste du Septième Jour en 1864. Elle sanctifie le dimanche. Elle enseigne la non-résurrection des impies et leur non-présence au jugement dernier. L’âme des impies est détruite après leur mort. Elle n’a que 34.000 membres dans le monde, dont 5 en France.

EGLISE ADVENTISTE EVANGELIQUE: Elle fut fondée en 1863. Elle sanctifie le dimanche. Elle croit à l’immortalité de l’âme. Elle est très large et en voie de disparition. Elle compte encore 11.000 adeptes dans le monde dont 2 ou 3 en France.

EGLISE DE DIEU : Elle s’est séparée 1865 de l’Eglise Adventiste du Septième Jour. Elle sanctifie aussi le dimanche au lieu du samedi adventiste. Pour elle, Ellen White n’a pas été inspirée divinement. Elle permet à ses adeptes de fumer un peu, de con-sommer un peu de vin et de café. Elle ne compte que 13.000 membres dont moins de 5 en France.

EGLISE ADVENTISTE DE L’AGE A VENIR : Elle naît en 1888, après une dispute au sujet du Règne de Mille Ans. Pour elle, ce règne a lieu sur la terre. Elle est toujours en train de calculer . le retour du Christ. Elle compte 8.000 adeptes dans le monde et 2 ou 3 en France.

l’union groupe plusieurs conférences. Plusieurs conférences forment une division. L’Eglise entière comprend douze divisions dans le monde, dont trois en Europe.

CULTE : Il a lieu le samedi matin dans des chapelles ou des salles qui portent souvent comme étiquette : «Vers la Lumière». On y chante des cantiques du recueil : «Hymnes et Louanges», fait des prières, lit un texte de la Bible que l’on médite. Le culte est précédé ou suivi d’une école du sabbat qui dure une heure. Pendant la semaine des réunions de prière ont lieu.

SACREMENTS : Les Adventistes ont deux sacrements : Le Baptême suit la repentance et la conversion, il est donné uniquement aux adultes par immersion totale. La Sainte-Cène est célébrée tous les trimestres, elle est précédée du lavement mutuel des pieds. Elle est administrée sous les deux espèces : morceaux de pain et petits verres de jus de raisin. Ce sont uniquement des symboles.

VUE D’ENSEMBLE : Les adventistes accordent beaucoup d’importance à la santé, à l’alimentation et à l’hygiène. Dans ce but ils disposent de

40.000 pasteurs, missionnaires, docteurs et infirmières,

235 hôpitaux, sanatoria, cliniques, maisons de repos, dispensaires,

4.870 écoles primaires et 306 écoles supérieures et maisons d’éducation, dans 197 pays.

Ils ont également 70 imprimeries, 45 maisons d’édition qui impriment 360 journaux en 200 langues et dialectes.

JOURNAUX: La ReVue adventiste, 16 pages, fondée en 1896, bimensuelle ;

La Traduction du Adventist Review and Sabbath Herald, mensuelle, 16 pages, fondée en 1946 ;

Jeunesse, pour les jeunes adventistes qui forment «les missionnaires volontaires», mensuelle, 32 pages, fondée en 1946 ; Signes des Temps, mensuel, 16 pages, fondés en 1876 ;

Vie et santé, fondée en 1890, mensuelle, 24 pages ;

Le moniteur, mensuel, 32 pages, fondé en 1946 ;

Leçons de l’Ecole du Sabbat, trimestrielles, 48 pages. IMPRIMERIE : Les Signes des Temps à Dammarie-les Lys, Seine- et-Marne. Presque tous les journaux, brochures et livres sont imprimés à cette maison d’éditions fondée en 1922. Elle publie surtout des livres spirituels, d’hygiène et d’histoires pour enfants.

EMISSION RADIOPHONIQUE : La Voix de l’Espérance, sur Radio Luxembourg, le lundi à 23 heures, sur Radio Monte-Carlo, le samedi à 18 heures 10, sur Paris-National, France III, le dimanche à 9 heures.

BROCHURES : Outre les livres, quelques brochures sont vendues par le porte-à-porte, ce sont : A ceux qui pleurent ; Les origines du dimanche; Où sont les morts?; Jour férié ou Jour de repos ? ; Baptême et Nouvelle Naissance ; La fin du monde est- elle proche ?

ŒUVRES : Cours de Bible par correspondance, Boîte postale 210, Paris VIIIe ; Studio d’enregistrement : Le Quatuor ; La voix de l’Espérance et Le Disque évangélique au centre parisien ; Société de bienfaissance Dorcas; Mission Intérieure Adventiste; Colonies de vacances ; Organisme Vie et Santé qui organise des conférences sur le jus de fruit;

Missionnaires volontaires, sorte de scouts adventistes ;

Maison de repos «Le Foyer» au Pignan, Hérault; Fabrique de produits diététiques «Pur aliment», 15, Rue Honnet à Clichy, Seine; Polyclinique «Vie et Santé» à Bordeaux;

Librairie «Le Soc», au centre parisien.

Cycles de Conférences: «Mystère ou Certitude?».

SEMINAIRE ; Les prédicateurs adventistes sont formés au Sémir naire de Collonges-sous-Salève, Haute-Savoie, près du Lac de Genève. Fondé en 1921, il est mixte. Il comprend des ateliers, une ferme, une imprimerie et un home d’enfants. L’emploi de temps est ridige et chargé.

DIFFUSION; U.S.A., Belgique, Suisse, Indochine, Canada, France, Italie, Allemagne, Suède, Norvège, Finlande, Grande-Bretagne, Roumanie, Irlande, Russie, Hollande, Bulgarie, Hongrie, Tchécoslovaquie, Espagne, Portugal, Autriche, Yougoslavie, Po-logne, Argentine, Brésil, Chine, Indes, Japon : en tout dans 230 pays.

CHAMPS DE MISSION ; Les missions adventistes sont très développées : Antilles, Afrique Occidentale Française, Madagascar, Réunion, Cameroun, Iles de l’Océanie, etc…

ADEPTES: Ils viennent aussi bien du catholicisme que du protestantisme. Ce sont surtout des employés, des ouvriers et quelques bourgeois, toujours des gens simples, des hommes et des femmes, les femmes dominent. Ils sont végétariens et s’abstiennent da l’alcool, de tabac, de thé, et de café. Chaque adepte donne la dîme de ses revenus à l’Eglise.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES DANS LE MONDE: 1.100.000.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES EN FRANCE : 4.000 baptisés et 6.000 sympathisants.

CENTRE FRANÇAIS : Union franco-belge des Eglises adventistes, 130, Boulevard de l’Hôpital, Paris XIIIe.

PRINCIPAUX LIEUX DE CULTE :

AUTRES LIEUX DE CULTE :

Antony, Auxerre, Annecy, Arcachon, Argenton-sur-Creuse, Aix- les-Bains, Angoulême, Avignon; Bolbec, Beauvais, Buhî, Blanc- sur-Indre, Belfort, Boulogne-sur-Mer, Brignon; Craon, Chante- nay, Calais, Chatellerault, Cannes, Caudéran; Epinal ; Fougères, Fécamp, Forges-les-Eaux ; Granville; Gundershoffen ; Jebsheim ; Le Mans ; Laval, Livron, La Mûre ; Lisieux, L’Etang ; Meudon, Mamers, Montbéliard, Moussac ; Nevers ; Orléans ; Parnot, Pfaffenboffen, Philippsbourg, Pierre-Segade, Pougnes, Pouilly- sur-Loire ; Redon, Remiremont ; Sées, Sainte-Croix-aux-Mines, Sainte-Marie-aux-Mines, Saint-Quentin, Saintes, Sélestat, Sens, Saint-Germain-Laval, Souternon, Saint-Julien, Saint-Hippolyte- du-Fort; Troyes, Tullins, Tallard, Thionville; Vitré, Vernon, Vimoutiers, Vichy, Villeneuve-lés-Avignon; Wasquehal.

Les ADVENTISTES RÉFORMÉS

NOM OFFICIEL s Eglise des Adventistes du Septième Jour, Mouvement de Réformation.

FONDATEUR : En publiant le livre : «Le Chrétien et la Guerre», J. WTNTZEN est excommunié de l’Eglise adventiste principale. Il fonde sa propre secte en 1914. Ses disciples se nomment Adventistes réformés. Ceux-ci reprochent aux autres Adventistes d’être trop larges et surtout d’être plus de 144.000. Cette Eglise se considère toutefois comme fille de l’Eglise Adventiste principale.

DOCTRINE : L’œuvre de Satan a corrompu toutes les Eglises. Seule l’Eglise Adventiste Réformée est le Petit Troupeau, la véritable Eglise du Christ. Elle observe le Sabbat (qui pour elle veut dire samedi). Dieu est appelé Jéhovah au lieu de Iahvé. La Réforme du XVI0 siècle a continué au début du XIXe siècle. Les adventistes réformés sont les 144.000 qui auront le sceau de Dieu à la venue du Seigneur, ils se considèrent aussi comme l’Israël spirituel. Depuis l’année 34, les Juifs ne sont plus le peuple de Dieu. Le dimanche a été inventé en 321. Les adventistes réformés luttent pour le rétablissement des Dix Commandements, la Sainte Loi de Dieu que les hommes, sous l’influence de Satan, ont changée. Les morts dorment jusqu’à la Résurrection au retour du Christ.

CONSEQUENCES DE LA DOCTRINE: Les adventistes réformés sont objecteurs de conscience. Ils refusent de faire tout travail le samedi, les enfants n’assistent pas aux cours ce jour.

FETE : La plus grande fête de la secte est la Lémuria qui se célèbre le 13 mai.

Un repas rituel est pratiqué à cette occasion.

EMBLEME : Deux étoiles à quatre branches.

JOURNAL: Le Temple d’Al.

DIFFUSION : France, Belgique (centre important à Bruxelles), Etats-Unis, Angleterre et Suisse.

LIEUX DE CULTE FRANÇAIS : Bordeaux, Lyon et Paris.

CENTRE FRANÇAIS : 27, Rue Bleue à Paris.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES : Les Alistes sont 1.500 dans le monde. En France, ils sont 85, dont 50 à Paris. Les hommes sont aussi nombreux que les femmes.

Les AMOUREUX

NOM OFFICIEL : Eglise d’Amour.

AUTRES NOMS : Religion vivante, Amour-Religion.

FONDATEUR : Edouard SABY. Il fonde sa secte en 1926. Il se présentait au monde comme Messager de Dieu et encore comme Annonciateur de la Bonne Nouvelle.

TRANSFORMATION: Le succès de ce mouvement fut très lent au début, aussi le fondateur a-t-il transformé son Eglise en une espèce de secte laïque qui est connue en France sous le nom bizarre de Studio Addéiste.

DOCTRINE : Dieu n’est pas le Père d’amour dont parle la Bible. Seul l’homme est capable d’aimer parfaitement et fidèlement. Les adeptes de cette Eglise d’Amour quittent leur communauté spirituelle, surtout catholique, pour adorer un bel homme on une belle femme. Ces beautés sont adorées à genoux.

DIFFUSION : Des membres dispersés se rencontrent dans toute l’Europe.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES DANS LE MONDE: L’Eglise d’Amour est très hostile aux statistiques. Elle-même ignore le nombre de ses adeptes. On peut toutefois les évaluer à 150.000.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES EN FRANCE : Seul le cercle de Paris existe encore avec une vingtaine de membres.

CENTRE : Cercle Edouard-Saby, 184, Bld. St-Germain, Paris.

ETYMOLOGIE : Le mot: anabaptiste vient de deux mots grecs: ana-de nouveau et baptizein —• plonger dans l’eau.

BEMARQUE : Ne pas confondre avec les Baptistes.

NOM OFFICIEL: Eglise Anabaptiste.

FONDATION ; Le mouvement anabaptiste est né au début du XVI* siècle, en marge de la Réforme. Dès 1520, il a de nombreux propagandistes : Conrad GREBEL, mort en prison ; Félix MANTZ, jeté dans une rivière; Simon STUMPF; Georges BLAUROCK de Zurich, mort sur un bûcher; Louis HOETZER de Saint-Gall; Balthasar HUBMAIER né en 1480 et brûlé vif en Allemagne le 10 mars 1528 ; Jean DENK ; Jean MATTHYS, un Hollandais qui annonce le Royaume des Saints à Munster en Westphalie ; Jean de LEYDE ; Nicolas STORCH ; Michel SATTLER né en 1500 et mort en 1527 ; Melchior HOFFMANN qui annonce en 1529 le Jour de l’Eternel et pour 1533 la descente de la Jérusalem Céleste à Strasbourg; Thomas MUNTZER né en 1490 et mort en 1525. Le centre d’origine est Zurich en Suisse.

DEVELOPPEMENT HISTORIQUE : Les Anabaptistes se séparen t de la Réforme protestante le 17 janvier 1525. Ils sont souvent persécutés et massacrés; plus de 100.000 sont tués entre 1530 et 1560. Ils participent à la Guerre des Paysans en 1524—1525. Le premier synode anabaptiste a lieu à Scblatt eu 1527. Un centre important sera Nikolsbourg.

C’est une secte fanatique et multiforme politico-religieuse et chialiste, c’est-à-dire qu’elle veut calculer le début du Millenium terrestre.

DOCTRINE : Elle est radicaliste, complexe et très variée. Le baptême des enfants est une invention satanique. On entre dans l’Eglise par le Baptême des adultes. La Cène n’est donnée qu’aux croyants. Le serment de fidélité à l’Etat est interdit. Le croyant est inspiré directement par le Saint-Esprit de sorte que la lecture de la Bible devient inutile. L’Apocalypse est le plus important et le plus parfait de tous les livres. La voix de Dieu se fait entendre directement dans l’oreille du croyant, c’est l’Onction du Saint-Esprit.

ORGANISATION ET CULTE : Les assemblées locales sont présidées par les diacres, les anciens et les évangélistes itinérants. Toutes les églises locales sont autonomes, mais unies toutefois par une

organisation synodale. Les assemblées peuvent excommunier les membres non fidèles. Les assistants des cultes sont surtout des paysans.

DIFFUSION : Allemagne, Suisse, Italie, Tchécoslovaquie, F rance, Hollande, Angleterre, Scandinavie et Pologne.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES DANS LE MONDE : 200.000.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES EN FRANCE: 110.

LIEUX DE CULTE: Belfort, Rue du Docteur Petitjean; Bricou-lès-Châteauvillain, Haute-Marne ;

Metz et environs ;

Reims ;

Stosswihr, Haut-Rhin.

Les ANGÉLISTES

NOM OFFICIEL : Eglise du Culte des Saints-Anges.

ORIGINE : Cette secte qui ne veut pas avoir de fondateur est issue du Catholicisme au début du XXP siècle. Elle qualifie les Catholiques de Sacramentaux.

DOCTRINE : Elle se base surtout sur Genèse VI. Les Anges qui sont apparus comme Faunes, Dryades, Nymphes chez les Grecs et les Latins ou comme Vierge Marie et Notre-Dame chez les Catholiques, sont des dieux. Ces Anges-dieux sont éternels, in- créés. L’Antéchrist viendra bientôt car les Chrétiens n’adorent plus les Anges. Cet Antéchrist sera conçu par l’union des Incubes et des hommes.

ADEPTES : Ce sont surtout des femmes assez âgées. Ces adeptes prétendent avoir vu des «anges-succubes» et des «anges-incubes» sous la forme de petits hommes splendides, étincelants et merveilleux.

CULTES: Ils sont rares. Ils se font dans de simples salles où se trouvent de nombreuses statues d’anges avec de grandes ailes.

DIFFUSION : En F rance uniquement.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES: 15.

LIEU DE CULTE : Ces quelques adeptes vivent à Paris et se réunissent en privé une fois par mois.

NOM OFFICIEL: Communauté des Anonymes.

NOM ORIGINEL : Les Namenlosen. (Nom allemand qui signifie : ceux qui n’ont pas de nom).

AUTRES NOMS : Les Anomistes, les Sans-Noms, Disciples du Christ, Vrais Chrétiens, Amis (à ne pas confondre avec les Amis quakers), Deux à Deux.

FONDATION : Cette communauté difficile à définir a ses origines aux Etats-Unis. Les adeptes ne veulent porter aucun nom et n’avoir aucun fondateur.

DOCTRINE : Elle résume la Bible en deux versets : Romains X, 17 et Marc VI, 7 et ss. Les Anonymes sont les vrais messagers. Sans eux, le salut est impossible. Us admettent donc deux Sauveurs : le Christ et un Anonyme.

ADEPTES : Les adeptes sont désignés par la formule : «Il est sur le chemin I» Ils ne doivent accepter aucun salaire, être sans propriété, sans logis et sans femme. Les adeptes vont toujours deux par deux. Ils vivent de l’hospitalité. Us sont contre les bénédictions des pasteurs. Les Anonymes doivent obligatoirement quitter leur Eglise. Us refusent de faire le service militaire et s’opposent au baptême des enfants.

DIFFUSION : Suisse, France, Allemagne, Angleterre, Canada, Australie.

GENTRE EUROPEEN : Wahlendorf près de Berne en Suisse. Ce centre est dirigé par le cultivateur Hegg. Il est secondé par ses trois fils. Chaque année en juillet une mission sous la tente est organisée à Wahlendorf.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES DANS LE MONDE: 11.000.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES EN FRANCE: 40. Les Anonymes onL fait leur apparition en France en janvier 1957, en ouvrant un lieu de culte à Colmar (Haut-Rhin).

CHAMP DE MISSION : Une grande station missionnaire à Meknos au Maroc.

Les ANTICLÉRICAUX

NOM OFFICIEL : Société Secrète Catholique Anticléricale.

AUTRE NOM : Direction Centrale de l’Organisation du Laïcat.

REMARQUE : Il s’agit ici d’une secte qui est en même temps une société secrète.

FONDATION: Cette organisation a été fondée en Allemagne, à Munster, en Westphalie en 1905.

BUT : Son but principal est de fonder une société chrétienne de Culture pour l’Apostolat laïc. Les Anticléricaux veulent inaugurer un catholicisme sans clergé et même hostile au clergé. Leur premier but est de supprimer la Sacrée Congrégation de l’Index.

CONSEQUENCES : Les adeptes de cette secte ne fréquentent plus l’Eglise catholique, ne participent plus aux sacrements et refusent de se confesser.

CULTE s II se réduit à des réunions privées où l’on chante, prie et lit des extraits de la Bible.

DIFFUSION : Allemagne, France, Espagne, Italie, Portugal, Hongrie.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES DANS LE MONDE : 200.000.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES EN FRANCE : 400.

LIEUX DE REUNIONS : Centre important à Paris ; présences anticléricales à Lyon, Nice, Nantes et dans quelques autres grandes villes.

Les Anticléricaux agissent en secret, les adresses de leurs lieux de culte ne sont donc pas connues par les non-anticléricaux.

Les ANTIMAÇONNIQUES

NOM OFFICIEL: Ligue Française Antimaçonnique.

FONDATEUR : Le Commandant DRIANT fonde officiellement cette secte en 1913.

ORIGINE : Cette Ligue résulte de la fusion de la Ligue Antimaçou- nique qui ne comprenait que des hommes, de la Ligue de Jeanne d’Arc qui ne comprenait que des femmes et de la Ligue Nationale de Défense contre la Franc-Maçonnerie de Mr. Copiu- Albaneelli.

REMARQUES : Le Commandant Driant a fondé d’autres petites sectes qui sont appelées couramment les Ligues Oriant. La Ligue Française Antimaçonnique est donc aussi une Ligue Driant.

BUT : Comme l’indique le titre de ces sectaires, ils combattent en secret les Francs-Maçons qui sont les émissaires du Diable. Leur doctrine est la négation et l’opposé de la doctrine des Francs- Maçons.

ADEPTES : Ils sont très prudents et circonspects, ils doivent faire un serment contre la Maçonnerie, ils ne doivent pas divulguer leur Statut et leurs lieux de réunion.

DIFFUSION : Dans presque tous les pays, doue aussi en France.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES DANS LE MONDE: 150.000.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES EN FRANCE : 250.

CENTRE FRANÇAIS: 33, Quai Voltaire, Paris.

Anciennement : 46, Rue de la Victoire, Paris.

Les ANTOINISMES

NOM OFFICIEL: L’Eglise antoiniste.

FONDATEUR: Antoine LOUIS, cadet d’une famille de 11 enfants, né à Mons-Crotteux, près de Liège, Belgique, le 7 juin 1846, et mort le 25 juin 1912 à Jemeppe-sur-Meuse. Baptisé catholique, il fit sa communion solennelle. Jeunesse peu heureuse: ouvrier mineur dès l’âge de 12 ans ; voyage en Allemagne, Pologne et Russie ; ouvrier métallurgiste en Allemagne ; contre-maître en Pologne ; concierge à Jemeppe-s-Meuse aux «Tôleries Liégeoises», Se marie en 1873 avec Jeanne-Catherine Collon ; de ce mariage naît un fils anormal qui meurt en 1893. Malade d’estomac, Antoine lit le Livre des Esprits d’Allan Kardec qui le guérit. Avec son ami Gony, il s’intéresse au Spiritisme. Dès 1888, il guérit des malades grâce à son fluide guérisseur, fait tourner des tables et se découvre médium. Après 1904, condamné pour exercice illégal de la médecine, il no traitera plus qu’avec son fluide et l’imposition des mains, sans prescriptions de remèdes. Il prêche sa religion dès 1904. Entre 1906 et 1908, il reçoit des révélations les dimanches.

SURNOMS DU FONDATEUR : Le Père Antoine, Antoine le Gué-

risseur, Antoine de Ténébreux, Régénérateur de l’Humanité.

AUTRES TEMPLES : Bernay, Cherbourg-Octeville, Lyon-Villeurbanne, Monaco, Nantes-Chatenay, Nice, Orange, Saint-Etienne, Vervins, Vichy.

AUTRES PRESENCES ANTOINISTES : Aix-les-Bains, Angers, Annecy, Arcachon, Armentières ; Billy, Bourges, Bourgoin, Bri- onne ; Caudry, Carvin, Château-Gontier, Couptrain, Croix, Denain, Dieppe, Domène, Douai; Firminy; Grenoble; Haut- mont, Houplines ; Jallien ; Labriquette, Lachapelle-d’Armen- tières, Lecelles, Le Havre, Libercourt ; Mantes, Marle-sur-Serre, Meulles ; Nîmes ; Oignies, Orbec, Orléans ; Rennes, Rouesné- Vassé ; Sablé, Saint-Aubin-le-Cary, Serqueux, Solesmes, Sotte- ville ; Toulouse, Tourcoing; Valenciennes, Varennes.

Les ANTONIENS

NOM OFFICIEL : Eglise Chrétienne Universelle Antonienno.

REMARQUE: Lee Antoniens ne doivent pas être confondus avec les Antoinistes.

FONDATEUR : Antoine UNTERNAEHRER, né à Schupfheim, prèß de Lucerne en Suisse, en 1759. C’était un charlatan. Il fut baptisé catholique et fit sa première communion. Très jeune, il quitte sa région natale pour s’installer dans l’Oberland bernois, d’où il partira comme missionnaire de sa doctrine spéciale au début du XIXe siècle.

DOCTRINE : Antoine Unternaehrer est le Christ revenu sur la terre pour sauver définitivement. Le monde était perdu parce qu’il ne mettait pas bien en pratique le plus grand commandement de tous les temps : «Croissez et multipliez-vous !»

CONSEQUENCES DE LA DOCTRINE : Dès l’origine de la secte, la police et les asiles d’aliénés doivent intervenir.

La doctrine aurait aussi donné naissance à ï’«esthéticisme», à l’hygiène et au traitement «air-lumière-soleil».

ADEPTES : Leur nombre va en diminuant d’année en année. Le« femmes sont plus nombreuses que les hommes.

DIFFUSION : Suisse, Allemagne et France.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES DANS LE MONDE: 850.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES EN FRANCE : Ils ne doivent pas être plus de 5. On les trouve dans le Jura près de la frontière shiisse. Ce sont des bûcherons très âgés.

Les APOSTOLIQUES

NOM OFFICIEL : Eglise Catholique Apostolique.

AUTRE NOM s Les Irvingiens.

REMARQUE : A ne pas confondre avec les Apostoliques pentecôtistes.

FONDATEUR; Edouard IRVING, né le 4 août 1792 à Annam, au sud de l’Ecosse; mort à Glascow, le 8 décembre 1834. Etudiant à Edimbourg ; Professeur de Mathématiques ; Recteur de l’Académie de Kirkaldy; Etudiant en Théologie; Prédicateur auxiliaire à Glascow en 1819 ; Pasteur de la communauté presbyté-rienne écossaise de Londres en 1822, où il prêche souvent sur l’Apocalypse.

ORIGINE ; Le banquier londonien Henry Drummond organise dès 1826 des réunions de prière pour la réforme des Eglises. Irving y assiste. Il se croit prophète et accuse les Eglises d’être la Babylone. Exclu de l’Eglise d’Ecosse le 2 mai 1832, Irving installe une nouvelle église dans la Newman-Street à Londres. Ce sera la première église apostolique.

Pendant les voyages missionnaires d’Irving, une de ses fidèles Marie Campbell se met à parler en langues en plein culte, le 21 mars 1830 à Fernicarry. C’est Cardale qui explique ce phénomène.

BUT DU FONDATEUR : Reconstitution du Corps du Christ avec les ministères conformes au Nouveau Testament : apôtres, évêques, anges, anciens, prophètes, évangélistes, pasteurs et docteurs; diriger l’Eglise par 12 élus du Saint-Esprit, successeurs des apôtres.

PRINCIPALE ŒUVRE DU FONDATEUR: L’ouvrage théologique :

«Babylone et l’incroyance aux prophéties de Dieu» (1826).

DEVELOPPEMENT HISTORIQUE: Le 31 octobre 1832 Cardale est élu premier apôtre par le Saint-Esprit. En 1834 ce sont 5 et en 1835 les 12 apôtres. Le 17 juin 1835 se réunit le premier Concile des 12 apôtres au château d’Albury en Angleterre. Ceux-ci partiront pour évangéliser le monde le 14 juillet 1835. Cette date marque la fondation de la nouvelle Eglise. Ces apôtres doivent préparer le retour du Christ qui régnera alors mille ans sur la terre.

Après la mort d’Irving, le théologien allemand Thiersch organise la secte. Le 3 février 1901, meurt le dernier apôtre Wood- house à Albury, ce qui arrête les consécrations et les impositions du Saint-Scellé.

ORGANISATION : Au sommet du mouvement sont les apôtres, de vrais dictateurs, jusqu’en 1901. Ils commandent à tous les ministres. Depuis, ce sont les anciens, tous égaux, qui assurent les services cultuels.

Irving ne fut pas apôtre, il fut seulement : ange !

PLUS GRANDE FETE : Le 14 juillet, anniversaire du départ en mission des premiers apôtres irvingiens. Les autres fêtes chrétiennes sont célébrées.

DOCTRINE: Infidélité de toutes les Eglises. Retour imminent du Christ, retour avancé par le choix des 12 apôtres.

La chair du Christ est pareille à la nôtre, même dans le péché et dans le mal. Christ n’est donc qu’un Martyr et non le Rédempteur.

PREVISIONS DU RETOUR DU CHRIST: Irving et ses apôtres ont prévu le retour du Christ successivement pour le 14 juillet 1835, pour le 25 décembre 1838, pour le 14 juillet 1842, pour le même jour en 1845, 1855 et enfin 1864.

CATHQLICISATION DE LA SECTE : Lentement le culte et la doctrine évoluent vers le catholicisme. Furent admis :

1847: une longue liturgie et l’extrême-onction; 1848: génuflexion devant l’hostie; 1850: transsubstantiation; 1851: eau bénite, cierges et dévotion à Marie; 1852: les sept sacrements catholiques.

SACREMENTS : Ils tiennent une très grande place, ils sont nécessaires au salut : Baptême par immersion, confirmation, eucharistie, pénitence, extrême-onction, ordre et mariage.

RITES : Deux grands rites : l’Imposition du Saint-Scellé qui marque les vrais enfants de Dieu. L’onction d’huile et du Saint-Chrême, faite par les apôtres sur le front des 144.000 scellés. Ceci est préconisé par Cardale dès 1847, c’est la seule condition pour avoir le Saint-Esprit.

CULTES : Ils ont lieu le dimanche matin, avec un grand faste, de l’encens. Utilisation de vêtements sacerdotaux. Au cours des cultes se manifestent les charismes miraculeux de l’Esprit, des guérisons, des visions, des révélations, le parler en langues, des uttérances (révélations spéciales reçues directement du Saint- Esprit). Tout ceci est accompagné d’un enthousiasme exagéré et d’exaltations prophétiques. Culte proche du culte anglican et catholique.

LIEUX DE CULTE FRANÇAIS : De rares chapelles, quelques réunions privées, groupements assez secrets. Les adeptes sans lieu de culte participent quelquefois aux cultes des grandes Eglises.

ADEPTES : Ce sont des gens simples qui font peu de prosélytisme, ce sont surtout des paysans, 60 % de femmes et 40 % d’hommes.

DIFFUSION: Allemagne (surtout Bavière), Suisse (centre: 107, Freistrasse, Zurich VII), Grande-Bretagne, Danemark, Irlande, France, Italie, Etats-Unis, Nouvelle-Zélande, Australie, Canada.

CENTRE MONDIAL : Catholic-Apostolic Church, Bradfort, Angleterre.

PRINCIPAUX LIEUX DE CULTE FRANÇAIS : Paris, 15% 27, Rue François-Bonvin ; Strasbourg, 9, Rue de Niederbronn; Mulhouse, 19, Passage des Augustins.

AUTRES REGIONS DE PROPAGANDE : Alsace, Lorraine, Cam- brésis.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES DANS LE MONDE : 60.000.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES EN FRANCE : 80.

CHAMPS DE MISSION: Chine, Indes, Japon.

Les AQUARISTES

NOM OFFICIEL : Communauté Aquariste.

FONDATEUR : Magi AURELIUS, né au début du vingtième siècle. Il est aussi le seul prêtre de cette secte.

DOCTRINE : Jésus n’est rien d’autre qu’un grand astrologue. Le monde et le temps sont divisés en sept périodes appelées les sept ères de l’humanité. Nous vivons actuellement dans l’ère du Capricorne. Pour d’autres Aquaristes, il y a douze ères. L’ère du Verseau doit commencer bientôt, ce sont les Aquaristes qui préparent cette ère.

CREDO : Le seul article important de la foi aquariste est :

«Nous espérons tout de l’ère du Verseau!»

DIFFUSION : Uniquement en France.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES: 10.

LIEU DE REUNION : Ces quelques Aquaristes se réunissent chez leur fondateur dans la Rue Royale à Paris.

Les AROTISTE

NOM OFFICIEL : Alliance Universelle Arot.

FONDATRICE: Maryse CHOISY.

DOCTRINE : C’est un vaste mélange de Christianisme, de Boud-

dhisme, d’Esotérisme, de Yoga, d’Alchimie et d’Astrologie.

BUT : Cette secte veut mettre en pratique les Sciences Initiatiquce

pour élever spirituellement tous les habitants de la terre.

ADEPTES: Les adeptes doivent suivre un enseignement et faire certaines épreuves pour être admis. Cette secte est ouverte à tous. Les adeptes sont courtois, ils s’entre-aident, ils sont très tolérants. Ils portent la Croix de Saint-André et le X qui signifie pour eux: Xoné (creuset), Xrusos (or), Xronos (temps).

SACREMENT : Les Arotistes n’admettent qu’un seul sacrement : le Baptême de Feu.

SYMBOLE : Trois cercles où sont inscrits les lettres A — fern, R = air, O = eau et T = terre. Ce symbole peut alors se lire : Rota (roue)

Tora (loi) et Taro (tarot).

Ce jeu a inspiré un autre fondateur de secte Georges Roux de Montfavet.

DIFFUSION: Uniquement en France.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES : 45.

LIEU DE CULTE : Le seul lieu de culte connu est situé 15, Rue Lord Byron, à Paris.

DISSIDENCE : Les Amis de Maryse Choisy, 26, Rue Bayard, Paria.

Les ARROSÉS

REMARQUE : Le surnom d’Arrosés est donné à une secte pentecôtiste outrancière.

NOM OFFICIEL : Eglise de Pentecôte «Latter Rain».

AUTRES NOMS: Mouvement de l’Evangile intégral, Le Vrai Libérateur, Les Vrais Pentecôtistes.

FONDATEUR : W.-J. SEYMOUR, un pasteur méthodiste nègre. Pendant une Campagne d’Evangélisation dans une petite chapelle de la Rue Azusa à Los Angeles, il reçoit le Saint-Esprit et parle en langues. D’autres frères l’imitent. Ceci se passa le 9 avril 1906. Bientôt le mouvement se répand en Europe sous le nom de : Croisière Missionnaire d’une vie profonde pour l’Europe.

DOCTRINE : Le troisième article du Symbole des Apôtres ne doit plus se prier : Je crois au Saint-Esprit…, mais : Je sens le Saint-Esprit. Les Arrosés croient que le don. du Saint-Esprit est réservé à eux et qu’il constitue la pluie de l’arrière-saison prévue dans Joël 11, 23. Le titre de «Latter Rain» fait penser â ce point de doctrine. L’imposition des mains et l’onction d’huile sur la tête et le corps des adeptes leur confère des visions, ils entendent des voix, parlent en langues et guérissent les malades. Le don du Saint-Esprit donne aux hommes le même pouvoir qu’aux apôtres : le don de faire des miracles. Seulement ceux qui parlent en langues sont sauvés. En se basant à tort sur les passages : Osée VI, 3 ; Zacharie X, 1 et Jacques V, 7, les Arrosés prétendent que la fin du monde est très proche. Ils cultivent aussi un prophétisme exagéré. La Pentecôte du Livre des Actes est complétée par celle d’aujourd’hui, les preuves en sont les visions, les directions et les ordres de l’au-delà : cela frise l’Occultisme.

ECHECS : Dès le début cette secte eut un vif succès, tout en présentant des dangers psychiques et physiques. Dès 1913, l’échec des prophéties et les crises de quelques membres (folie, détraquement cérébral, attaques de possession) fait régresser la secte.

PARLER EN LANGUES : Les cultes sont de vraies cacaphonies : tous, en même temps, parlent en langues. A titre d’indication, l’expression: «O Jésus!» se dit dans ce langage: «Tojé-tojéto!».

ARRIVEE EN FRANCE: Ce «réveil du Pentecôtisme» est introduit en France par le Canadien Owens. Dès son arrivée, il lutte contre les Assemblées de Dieu.

DIFFUSION: Allemagne, France, Angleterre, Suisse et Norvège.

CENTRE MONDIAL : Hôtel Rosut, Château d’Oex, Vaud, Suisse.

DIRECTEUR MONDIAL: J.-T. Owens.

CENTRE FRANÇAIS : 25, Rue Fondary à Paris.

RECUEIL DE CANTIQUES : Chœurs et Cantiques des Assemblées de Dieu en France. 40 pages.

ORGANISATION : Les Assemblées de Dieu sont opposées à toute organisation. Le Pasteur est élu par les fidèles qui lui fournissent des dons en argent. La Convention réunit les pasteurs et des Conférences mondiales se réunissent tous les trois ans pour une mise en commun des activités ; ces Conférences groupent des pasteurs et des laïcs.

JOURNAUX DE LA SECTE: Viens et Vois, mensuel, organe officiel, 16 pages, fondé en 1932, vient du 12 de la rue de Léveillé à Elbeuf, Seine-Maritime ;

La Onzième Heure, bimensuel, 4 pages, fondé en 1947, rédigé 10, Rue Marguerin à Paris et dirigé 30, Rue des Fontaines à Dieppe ;

Lumière du Monde, 18 pages, fondé en 1948, pour les jeunes, édité à Rennes, lu aussi par les Darbystes, bimestriel ;

Notre Vocation Céleste, mensuel, 3. Rue de la Motte-Fabiet, Rennes.

L’Etoile du Matin, pour enfants, fondé en 1951, mensuel, édité à Rennes, lu aussi par les Darbystes et d’autres ;

Cercle d’Etudes Bibliques, bulletin hebdomadaire.

EMISSION RADIOPHONIQUE : Radio-Réveil, le jeudi sur les antennes de Radio Monte-Carlo.

DISQUES : Les Assemblées de Dieu ont fait enregistrer des cantiques de Réveil à quatre voix édités par Radio-Réveil.

ACTIVITÉS : Grands meetings interrégionaux ou internationaux à la Salle Wagram à Paris ou au Vélodrome d’Hiver, par exemple; camps de Jeunesse et colonies de Vacances.

CENTRE MONDIAL: Springfield, Missouri, U.S.A.

DIRECTEUR MONDIAL : Rév. Arthur-G. Osterberg, superintendant de district pour les Assemblées de Dieu.

ARRIVÉE EN FRANCE : Invité par une Suissesse M. Biolley, le premier pentecôtiste, l’Anglais Douglas Scott débarque en France, à Le Havre, fin 1929.

CENTRE FRANÇAIS : 47, Rue de la Cour-des-Noues, Paris XX ».

DIFFUSION EN FRANCE : Tout le pays, mais principalement la Normandie, le Nord et le Midi.

ECOLE BIBLIQUE : Les pasteurs pentecôtistes sont formés dans l’Ecole biblique de Vincennes.

ADEPTES : Ils viennent de toutes les classes, mais les simples gens, le milieu ouvrier, petit commerçant et employé domine. Ils proviennent en grande majorité du catholicisme. Ils sont orgueilleusement anti-œcuméniques. Ils s’abstiennent de cinéma, de tabac et d’alcool.

DIFFUSIONS Suède, Belgique, Autriche, Bulgarie, Finlande, France, Allemagne, Grande-Bretagne, Hongrie, Brésil, Panama, Italie, Norvège, Pologne, Roumanie, Suisse, Russie, Chine, Indes, Chili, Pérou, Indonésie, Japon, Philippines, Etats-Unis, Canada, Congo-Belge, Libéria, Nigéria, Argentine, Mexique et dans pres-que tous les autres pays.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES DANS CE MONDE: 4.000.000.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES EN FRANCE : 22.000.

PRINCIPAUX LIEUX DE CULTE : Aix, Rue de la Glacière ; Angers, 62, Rue Jules-Guitton ; Caen, 7, Avenue de Tourville ; Calais, 93, Rue Vauxhall; Cannes, 12fcist Rue du Dr Calmette; Cannes, 3, Rue Edith-Cavell; Dieppe, 194, Grand’Rue; Dijon, 9, Rue Vivant-Carion ; Lille, 68, Rue Henri-Kolb; Lyon, 11, PL Croix-Paquet; Mantes, 25, Avenue Division-Leclerc; Marseille, Place de Sébastopol ; Nice, 4, Boulevard de Cimiez ; Nîmes, Rue Desjardins; Rouen, 60, Rue de Cauville; Toulon, 11, Boulevard Alata ; Tours, Rue Montbazon et Grenoble, 17, Rue Jean- Jacques-Rousseau et 88, Bld. de Metz à Roubaix.

AUTRES PRESENCES D’ASSEMBLES : Argenteuil, Avranches, Ange, Avignon, Aspres-sur-Biëch, Àngoulême, Antibes, Aurillac, Aubagne, Arles, Anduze, Alès, Albi, Agen, Amiens, Abbeville, Auneuïl, Aubenton, Arras ;

Broglie, Barentin, Beauvais, Billy-Montigny, Boulogne-sur-Mer, Blanc-Misseron, Bron, Beausoleil, Brive, Béziers, Bègles, Bordeaux, Blanc-Mesnil, Brest, Berville, Burey;

Champigny-sur-Marne, Carbaix, Chantenay, Coutances, Cor- melles, Carbillon, Conches, Caudebec-en-Caux, Carvin, Crespin, Cbulus, Cbalon – sur – Saône, Cagnes « sur – Mer, Cassis – sur – Mer, Carcassonne, Gastelnaudary, Castres;

Dunkerque, Dorignies, Décines, Draguignan, Dinard, Deauville, Dives ;

Equerauville, Elbeuf, Envermeu, Eu, Embrun-des-Alpes ; Fontenay-sous-Bois, Faverolles, Famars;

PRINCIPAUX LIEUX DE CULTE: Nord, Pas-de-Calais surtout à Barlin, Divion et Lille.

LIVRES DIFFUSES PAR LA SECTE : Le Divin Plan des Ages (494 pages). — La Manne céleste et culte quotidien (382 pages). — Les figures du Tabernacle (184 pages). — L’Enfer de la Bible (74 pages). — Hymnes de l’Aurore millénaire (350 cantiques). — Deux Etudes dans les Ecritures. —• Poèmes de l’Aurore. — Aurore, deux études et méditations bibliques (400 pages). — Voici votre Roi (112 pages). — La Vie, la Mort et l’Au-Delà.

BROCHURES DIFFUSEES PAR LA SECTE : Pourquoi Dieu a-t-il permis le mal ? — Où sont les Morts ? — La Vie et l’Immortalité ou le Salaire du péché. — Dieu et la Raison. —• Quand le pasteur Russell mourut. — Lumière dans la Nuit. — La pro-phétie de notre temps. — Résumé sur l’Enfer de la Bible. — Le Remède de Dieu. — Espérance? — Que sont devenus nos bien-aimés ? — Savez-vous ? — La Grâce sublime. — Quand ui« homme expire que devient-il ? — Qu’est-ce que l’Ame ? — La Résurrection des morts. — Le Spiritisme est du Démonisme. — Le Plan de Dieu-Jésus, Sauveur du monde, comment viendra la délivrance? — Le Retour du Christ. Quand et comment? — Père, Fils et Saint-Esprit. — Le ciel et le Paradis, que sont- ils, et où ? — Où allons-nous ? — La Parole devint chair . — Le Marchepied de Jéhovah rendu glorieux. — Message de la plus grande aurore millénaire.

JOURNAUX PUBLIES PAR LA SECTE: Aurore, Héraut de la Présence du Christ, annonce l’établissement du Royaume de Dieu sur la terre, parait depuis 1947, mensuel, imprimé à Cahors ; La Vérité présente et Héraut de l’Epiphanie, parle de la manifestation du Christ, bimestriel, imprimé à Lille.

Les adeptes français lisent encore les bulletins suisses publiés par Aurore à Prilly-Lausanne.

EMISSION REALISEE PAR LA SECTE : Radio Monte-Carlo, les mardis à 21 h. 10 : Pierre et Thomas.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES DANS LE MONDE: 34.000.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES EN FRANCE: 480.

SECRETARIAT DE LA SECTE : Association des Etudiants de la Bible «Aurore», Mr. T. Pilarski, 114, Rue Pierre-Legrand à Lille, Nord.

BAHAI

NOM OFFICIEL : Communauté universelle de Bahai.

FONDATION : En 1844, en Iran, Mirza Ali Mohammed qui se nomme Bab, annonce qu’il est le Précurseur d’un grand fondateur de religion. Il est fusillé le 8 juillet 1850.

Mirza Husein Ali se croit être le fondateur annoncé. Il est né le 12 novembre 1817 à Nun près de Téhéran, en Perse, comme fils de ministre. Il voyage beaucoup, visite Bagdad, Andri- nople et Acca. Il se révèle en 1853 et prend le nom de Baba’o’ilah. En 1868, il écrit au Pape Pie IX, à la reine Victoira d’Angle-terre, à Napoléon III et au czar Alexandre II pour leur annoncer qu’il est l’Apparition Divine et le Consolateur. Il soutient une énorme correspondance. II meurt le 28 mai 1892.

Son fils Abbas Effendi qui se nommera Abdoul Baha, né le 23 mai 1844 à Téhéran, lui succédera. II vient à Paris pour exposer sa doctrine, et meurt le 28 novembre 1921 à Acca.

LIVRES DE DOCTRINE: «Le Livre de la Loi» et «Mots Cachés», tous deux de Baha’o’llah.

BUT DU FONDATEUR : Construire la Nouvelle Jerusalem sur la terre. Unir toutes les religions en une religion bahaïste universelle. Créer un Tribunal universel, une langue universelle et lutter contre la guerre.

DOCTRINE : C’est un mélange d’Islam schiitique orthodoxe, de théosophie et de christianisme. Les deux sexes sont égaux en droits. La paix mondiale humaine est possible. L’amour du prochain conduit au salut. Baha’o’llah est Dieu venu sur la terre. Il est question de lui dans Proverbes IV, 14 ; Esaïe XL, 3 ; Esaïe XLII, 2; Daniel IX, 25; Marc XII, 6 et Jean XVI, 13. Jésus est un Christ, Baha’o’llah en est un autre. L’ère du Royaume de Dieu d’après Daniel XII, 6-11 a commencé en 1844. L’âme de l’homme est successivement minérale, végétable, animale et divine.

Toutes les religions doivent être tolérées, elles sont toutes égales et vraies. Le mariage est obligatoire. Le Royaume de Dieu est terrestre, les plus grands maux de l’humanité sont la mendicité, l’esclavage et le jeu.

FORMULE TRINI’l’AiRE : Au nom du Saint-Bab, du Saint- Baha’o’llah et du Saint-Abdoul Baha, Ainsi soit-il.

CHIFFRES SAINTS: 9 et 19.

CONSEQUENCES DE LA DOCTRINE: Modification du Notre- Père, suppression de : «Pardonne-nous nos offenses. Ne nous induis pas en tentation. Délivre-nous du mal».

Communauté sainte, parfaite; orgueil des bergériens qui jugent sans pitié et sans charité les Eglises ; pharisaïsme. Anti-œcuménisme.

Rejet des listes de membres.

SACREMENTS : Deux : le baptême des adultes et la sainte-cène pour les convertis.

DIFFUSION : Suisse, Allemagne et France.

CENTRES : Stuttgart-Vaihingen et Kalchofen dans l’Emmental en Suisse.

PRINCIPAUX LIEUX DE CULTE : Steffisbourg (4.800 adeptes), Schaffhouse.

NOMBRE DE LIEUX DE CULTE: 195 dont 103 en Suisse et 92 en Allemagne, surtout en Allemagne du Sud.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES DANS LE MONDE: Environ 110.000 membres communiants, en plus 6.500 sympathisants.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES EN FRANCE : 12 disséminés en Alsace, surtout dans le Haut-Rhin, Mulhouse, Colmar, Saint-Louis, Riedis- heim, mais sans lieu de culte.

PRINCIPAUX ADEPTES : Surtout des paysans, quelques rares employés, pas d’intellectuel.

JOURNAL DES BERGERIENS : En allemand, le «Messager de la Paix pour les Enfants de Dieu et pour ceux qui désirent le devenir», créé en 1918. Lu par les rares adeptes d’Alsace.

CHAMP DE MISSION : Nouvelle-Guinée.

TENDANCE : Depuis avril 1950, certains membres prient le Notre- Père intégralement.

Les BIOCOSMIQUES

NOM OFFICIEL : Alliance Universelle Biocosmique. FONDATEUR: Félix MONIER, fonctionnaire et astronome à Cha- tenay-Malabry, Seine. Il croit trouver dans les astres la base d’une nouvelle religion. Elle sera fondée en France en 1926. Il a de nombreux collaborateurs pour l’édification de la nouvelle communauté spirituelle. Les plus influents sont : A. L. Herrero de Mexico, A. Mary de Paris et A. Zucca de Rome.

BUT DU FONDATEUR: Il veut grouper dans une alliance tous les hommes et femmes devenus athées, de bonne volonté pour lutter sans relâche contre la barbarie et la bassesse de ce monde. Cette lutte doit se faire par l’intelligence, la solidarité et le bonheur.

DOCTRINE : Toutes les religions qui croient en un dieu ou en Dieu sont fausses. Il n’y a que quatre grands péchés : l’égoïsme, l’injustice, la méchanceté et la sottise. Seule la religion biocosmique a la force de transformer le monde, de créer par sa lutte contre la superstition et l’égoïsme, une humanité nouvelle. Le monde est éternel et incréé. L’Alliance Cosmique est immortelle. L’homme se sauve par sa propre puissance, par l’Amour de la Vie. L’homme est un mélange d’âme, de matière, de bien et de mal. L’âme humaine est issue d’une âme universelle à laquelle elle retournera. La mort est une métamorphose et l’homme est une parcelle de la Vie Universelle.

L’Alliance Biocosmique est une religion naturienne.

JOURNAL : Le petit bulletin : «La Vie Universelle».

DIFFUSION : France, Italie, Etats-Unis et Mexique.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES DANS LE MONDE : 3.500.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES EN FRANCE; 50 qui habitent surtout

Paris.

Les BIZZARE

REMARQUE : Il s’agit ici d’un groupement qui est à la fois une société secrète et une secte.

NOM OFFICIEL : Ordre Indépendant des Compagnons Bizarres.

NOM ORIGINEL ; Indépendant Order of Odd Fellows.

FONDATEUR : Thomas WILDEY fonde cette secte en Angleterre, en 1817.

DOCTRINE *. Dieu a échoué dans sa mission, c’est l’homme qui doit bâtir le Royaume divin sur la terre. La doctrine a été condamnée par le Vatican, le 20 juin 1894.

CONSEQUENCES DE LA DOCTRINE: Les Bizarres visitent beaucoup les malades et aident les orphelins et les pauvres.

DEVISE : Amitié, Fraternité et Vérité.

RESPONSABLE LOCAL: Emile Habert, Oberseebach.

JOURNAL : Paroles de Vie.

DOCTRINE : Elle ressemble à celle des Darbystes. Elle est puritaine, piétiste à outrance et anti-médicale.

Les BUCHMANISTES

NOM OFFICIEL: Réarmement Moral (RAM).

NOM ORIGINEL: Moral Rearmement (MRA).

AUTRES NOMS: Mouvement d’Oxford, Groupe d’Oxford, Oxfor- distes.

REMARQUE : La doctrine est sectaire, mais les membres ne le sont pas.

FONDATEUR : Frank BUCHMAN, né en 1878 aux Etats-Unis d’une famille d’origine suisse. A 24 ans, il est pasteur-luthérien et ceci pendant trois ans à Philadelphie. Il fonde un hospice pour pauvres enfants, il sera son directeur jusqu’à sa démission en 1908. Il voyage en Italie et en Angleterre où il a une vision au cours d’une réunion pentecôtiste. Après, il se considère comme le seul homme qui a été chargé par En Haut de changer le monde. Il se considère comme l’homme guidé par le Saint-Esprit. Vers 1920, il démissionne de sa fonction de pasteur et se fixe à Oxford. De là, il lance en 1921 un appel à la vie évangélique parfaite sans dogmatique.

DOCTRINE : La face du monde changera par suite du changement de cœur individuel. Les hommes sont responsables de l’humanité. Le monde peut être refait en changeant les hommes. Le monde sera rénové moralement sur la base d’une piété pratique centrée sur quatre impératifs catégoriques et absolus. Les Eglises sont sur un mauvais chemin, car elles n’enseignent que la religion impersonnelle. Christ est un modèle et non le Sauveur. Les grands maux des hommes sont l’impureté et la cupidité. Le Saint-Esprit parle uniquement dans les moments de silence, et non par la prédication ou la lecture de la Bible.

BUT : Empêcher les conflits entre nations, convertir les communistes.

ARRIVÉE EN FRANCE : Officiellement le 4 juin 1938.

OUVRAGES DE DOCTRINE: Refaire le monde, de Frank Buch- man, préfacé par Robert Schumann; Le monde reconstruit, de Peter Horvard, Edit. : Julliard, Paris ; F. Buchman et ses

Amis, de Aymond de Mestrei, Ed. Payot, Paris ; Ma vio a com- mecé hier, do Stephen Fout, Ed. Plon, Paris.

DEVISE: Les cinq C: Conviction, Contrition, Confession, Conversion, Continuance.

ADEPTES : Gens plutôt aisés, milieu politique et industriel surtout ; hommes et femmes, de toute race, classe, religion : ils acceptent des confucianistes, des athées, des catholiques, des protestants, des juifs, des musulmans et des bouddhistes. Les adeptes chrétiens fréquentent encore presque tous l’Eglise.

PROMESSES : Les adeptes promettent de conformer leur vie à une honnêteté absolue, un désintéressement absolu, une pureté absolue et un amour absolu. Ils doivent faire un recueillement quotidien d’un quart d’heure, le «partage», la chirurgie de l’âme, l’heure de silence, l’abandon à l’Esprit-Saint et des confidences réciproques.

REUNIOiVS: Dans des lieux de culte, des salles de conférences, d’hôtel ou ch.ee; des particuliers.

ACTIVITÉS : Ecole de formation à New-York qui forme les «ouvriers» salariés ; Organisation de house-parties, de maisons de vacances, de meetings, de Jamborees internationaux ; Démarches auprès des gouvernements.

DIFFUSION : Grande Bretagne, Norvège, Suède, Canada, France, Etats-Unis, Hollande, Australie, Nouvelle Zélande, Indes, Suisse, Belgique.

CENTRE MONDIAL : Oxford.

CENTRE AMERICAIN : lie Mackinac dans le Lac de Michigan, aux Etats-Unis.

CENTRE EUROPÉEN: Ceux près de Montreux en Suisse.

CENTRE FRANÇAIS : 68, Boulevard Flandrin, Paris XVI*.

JOURNAL: Courrier d’information du RAM, bimensuel, 4 pages.

EMISSION RADIOPHONIQUE: Hebdomadaire, sur Radio Luxembourg, heure de diffusion variable. En ce moment, le lundi soir à 23 heures.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES DANS LE MONDE : 125.000.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES EN FRANCE : 3.000.

LIEUX DE CULTE : Ils louent des salles dans toutes les grandes villes : Paris, Lyon, Marseille, Nice, Strasbourg, etc…

CONCLUSION : Au sujet du RAM, Léon Pilate a écrit : «Il y a du bon et du nouveau, le bon n’est pas nouveau et le nouveau n’est pas boni»

Les CATHOLIQUES LIBÉRAUX

NOM OFFICIEL: Eglise Catholique Libérale de France.

FONDATEUR : Monseigneur WEDGOOD, ancien curé vieux-catholique en Angleterre. En septembre 1918, Monseigneur Wedgood qui veut réorganiser le Vieux-Catholicisme, rencontre Monseigneur Leadbester qui l’initie à la théosophie. Il en sortira l’Eglise Catholique Libérale.

DOCTRINE : C’est une synthèse de catholicisme, de modernisme, de théosophie et de gnosticisme. Le Christ a mené sur terre une vie occulte.

Marie est la Mère du Monde, la Vierge éternelle et la Mère des Mystères. Il y a deux christs en Jésus : le Christ individuel et le Christ universel. Jésus n’est qu’un homme divinisé comme Bouddha, Zoroastre et Moïse.

Les catholiques libéraux peuvent interpréter le Symbole des Apôtres chacun à sa guise. Ils croient aussi à la Réincarnation.

LIVRE DE DOCTRINE : La Science des Sacrements de Monseigneur Leadbester.

SUCCESSION APOSTOLIQUE : Les ministres du culte sont ordonnés validement aux yeux de l’Eglise Catholique Romaine. Leur succession apostolique remonte à Bossuet en passant par Monseigneur de Matignon, Dominique Varlet, Jean Meindaarts et Monseigneur Wedgood.

SACREMENTS : L’Eglise Catholique Libérale est très sacramenta- liste. Elle reconnaît sept sacrements : le baptême par aspersion des enfants, indispensable au salut; la confirmation, la pénitence, l’eucharistie, le mariage, l’extrême-onction et l’ordre. Aucun sacrement ne peut être administré après douze heures, car le flux magnétique est absent après cette heure.

CULTE : Il est proche du culte catholique romain. La messe est célébrée en français par un curé en soutane violette.

DIFFUSION: Angleterre, Hollande et France.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES DANS LE MONDE: 1.100.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES EN FRANCE : 105 qui sont tous sortis de l’Eglise Catholique Romaine.

CENTRE FRANÇAIS : 169, Rue de Rennes à Paris VI®, ancienne adresse: Ubis, Rue Schoelcher à Paris.

LIEUX DE CULTE: Lyon, Nice, Paris (paroisse St-Michel), Strasbourg, 3, Rue Ed. Teutsch.

TENDANCES : Deux tendances nettement opposées se sont fait jour dans la secte : la tendance théosophisante et la tendance catho- licisante; mais aucune division ne s’est produite encore.

Les CHEVALIERS

NOM OFFICIEL: Chevaliers de la Table Ronde.

FONDATEUR : L’Officier Anglais WHITE mort en 1917. Celui-ci place Leadbeater comme premier évêque de la secte. La secte est fondée en 1908.

DOCTRINE : Mélange de Christianisme et de Théosophie. Nos corps sont enveloppés d’auras. Dieu est le Grand Chef de la Hiérarchie des Grandes Ames. La doctrine s’inspire de Blavatski et d’Annie Besant.

SYMBOLE : Etoile à cinq branches.

DEVISE : Sois le Roi !

FETES : Les plus grandes sont : la Fête de la Lumière ; la Fête de la Fleur; la Fête du Salut; la Fête du Pain; la Fête du Sel; la Fête de la Consécration de la Lumière; la Fête de la Consécration de l’Epée.

MOT SACRE: Aum.

HIÉRARCHIE : A la tête se trouve le Chevalier-Chef qui a sous ses ordres les Chevaliers-voyageants, les Chevaliers-dirigeants, les Chevaliers-servants, les Ecuyers et les Pages.

CULTE : Il se fait dans des salles sombres avec des desservants en robes jaune clair.

ADEPTES : Surtout des hommes qui insistent sur la résignation, la justice, la franchise, la propreté et la pureté.

DIFFUSION : Grande-Bretagne, France et une vingtaine d’autres pays.

CENTRE MONDIAL : Londres.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES DANS LE MONDE: 10.500.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES EN FRANCE : 40.

SIEGE FRANÇAIS : 4, Square Rapp, à Paris, à la même adresse où siège la Société de Théosopie.

ADEPTES : Surtout des catholiques ; ils s’engagent par un serment, signé avec un liquide rouge devant symboliser le sang, de convertir le plus grand nombre d’hérétiques. Ils portent pendant le culte une robe noire. Ils portent un insigne avec un casque de chevalier, un triangle et un poignard.

CULTE : Il se célèbre tous les dimanches. Sur l’autel brûle un cierge, symbole de l’unité que réaliseront les Colombistes. Le ministre du culte est aidé de quelques servants. Les premiers servants de la secte furent Curran, Michel et Lawler.

ORGANISATION : La secte est dirigée par un Conseil qui a à sa tête le Capitaine de la Garde.

DIFFUSION : Etats-Unis, Canada, France.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES DANS LE MONDE : 8.500.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES EN FRANCE : 15, sans lieu de culte fixe.

Les COMMUNAUTAIRES

NOM OFFICIEL : Communauté des Chrétiens.

ORIGINE : C’est la branche plus ou moins chrétienne de l’Anthroposophie.

FONDATEUR: Frédéric RITTELMEYER, né à Dillingen en Souabe, en 1872. Il est pasteur luthérien en Bavière et à Stuttgart jusqu’en 1922. En 1921, des étudiants en théologie de Mar- bourg, rencontrent Steiner, le fondateur de l’Anthroposophie, qui organise une semaine théologique à Stuttgart. Certains de ces étudiants dont Rittelmeyer, constitueront la Communauté des Chrétiens.

DOCTRINE : Elle se base sur la Bible et les ouvrages de Steiner, commentés par Rittelmeyer. Le monde est, avec tout ce qu’il contient, matérialiste. Jésus-Christ est une grandeur cosmique. L’homme peut changer le monde. Il est un esprit parmi les esprits. La nature est spiritualisée et remplie d’esprits. Jésus est l’esprit du soleil. Les actions de Jésus sur la terre ne sont rien d’autre que les actions bienfaisants du soleil. Jésus s’unit à l’homme dans la Parole, la lumière et le pain. L’homme monte vers Dieu par étapes.

Grâce à Rittelmeyer, Steiner est redevenu la Seule Voie de l’Univers.

On perçoit dans la doctrine une reprise de la Sagesse primitive des héros germains Wotan, Frigga ainsi que de la mythologie de Baldur. La nature qui est habitée par les esprits de la lumière, est une puissance qui distribue la force et divinise l’homme.

La Communauté des Chrétiens veut être une Eglise du Salut et surtout l’Eglise de l’avenir.

CULTE : Il est un mélange des cultes protestant et catholique. Le point culminant du culte est la consécration de l’homme : l’Acte de Consécration de l’homme. Le culte est une sorte de messe. Les couleurs liturgiques, les vêtements sacerdotaux, l’encens tiennent une très grande place. Le culte se fait dans de simples salles. Sur l’autel est posée la Tête du Christ de Michel Ange. Un violon ou un piano accompagne les cantiques. Le prêtre est assisté de deux ministrants qui portent la Bible et l’encens. Le culte se fait dans la langue du pays. Le lieu de culte est éclairé par un chandelier à sept branches. Les quatre parties du culte sont les lectures bibliques, l’Offertoire, la Consécration et la Communion. Le culte est une nouvelle naissance pour ses participants.

SACREMENTS : La Communauté deB Chrétiens connaît les sept sacrements de l’Eglise Catholique avec une signification différente. Elle croit au renouvellement du sacrifice au cours de son Offertoire.

ORGANISATION: Frédéric Rittelmeyer est le Conducteur et le Patriarche de la Communauté des Chrétiens. Il a sous ses ordres les chefs-conducteurs, les conducteurs supérieurs et les conducteurs.

RITE : A la Pentecôte, cette secte organise une sortie, une rencontre de tous les membres d’une région, sur une colline pour entretenir le Saint repas du Graal. Pour la France, ces réunions ont lieu sur la Colline d’Oberhausbergen près de Strasbourg.

JOURNAL: La Communauté des Chrétiens, ne parait qu’en allemand.

DIFFUSION: Allemagne, Suisse, France.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES DANS LE MONDE : 90.000.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES EN FRANCE: 100.

LIEUX DE CULTE : Les membres se réunissent en petits groupes locaux, surtout en Alsace ; un seul lieu de culte important : Strasbourg, 3, Quai de l’Abattoir.

Les DARBYSTES ÉTROITS

NOM OFFICIEL: Assemblée des Frères.

AUTRES NOMS: Communauté Chrétienne, Frères Etroits, Frères Stricts, Frères de Plymouth, Régénérés, Frères Exclusifs.

FONDATEUR: John-Nelson DARBY, né en Irlande le 18 novembre 1800, mort en 1882. Il fait des études de droit, est avocat, puis consacré pasteur anglican en 1826. Il quittera l’Eglise Anglicane en 1828, car il met en doute la succession apostolique. En 1829, Darby prend part à Dublin, à des études bibliques dirigées par le dentiste A. N. Groves, ainsi que par John Walker. De petits groupes semblables sont fondés à Plymouth et à Bristol. Le groupe de Bristol est dirigé par Newton. En 1847, Darby se sépare d’eux pour fonder le Darbysme. En 1838, Darby est prédicateur plymouthiste à Genève, Lausanne et auprès des Vau- dois. Il fera là ses premiers disciples. En 1844, il vient en France et prêche à Montpellier et à Nîmes. Il est le chef incontesté de sa secte à partir de 1871.

OUVRAGES DU FONDATEUR : Les souffrances de Christ et d’un homme en Christ; Vues scripturaires sur la question des Anciens ; La Délivrance et non pas le pardon seulement ; La nature et l’unité de l’Eglise du Christ ; L’Eglise ; Coup d’œil sur divers principes ecclésiastiques ; Le culte ; Quelques développements nouveaux sur la formation de l’Eglise ; Le ministère considéré dans sa source, sa puissance et sa responsabilité ; De la présence du Saint-Esprit; Une excellente version de la Bible.

DOCTRINE : Lea Eglises ont apostasié. La vraie communauté n’a ni organisation, ni hiérarchie, ni pasteur, ni ordre ecclésiastique, ni confession de foi écrite. La fin du monde est très proche. La communauté darbyste est le vrai troupeau qui accueillera le Seigneur. Les Darbystes sont les élus qui seront bientôt enlevés. Les autres Eglises sont des maisons de Satan qui donnent la mort aux âmes. L’enlèvement invisible do l’Eglise aura lieu très bientôt. Il n’existe plus de ministère ecclésiastique authentique.

CONSEQUENCES DE LA DOCTRINE : Les Darbystes exercent une grande polémique contre les Eglises. Les femmes ne doivent pas se couper les cheveux. Le boudin est interdit. Les prédicateurs ne doivent pas se préparer. Ils veulent se préserver des souillures du monde, s’abstiennent de beaucoup de choses. Certains ne prient plus : «Que ton règne vienne», car le règne est déjà venu en eux ; ni «Pardonne-nous nos offenses», car certains prétendent ne plus pécher. Au zèle anti-ecclésiastique s’ajoute donc l’hostilité contre le monde, un rigorisme moral, un particularisme intransigeant et une perfection morale et spirituelle. Les Darbystes veulent constituer une communauté de confessants. Ils fuient les fonctions publics et ne votent pas.

CULTE : Il a lieu le dimanche matin, des études bibliques et des réunions d’évangélisation et de prière ont lieu pendant la semaine. Le culte est présidé par un Ancien. Pour le culte les uns ont des dons et les autres ont des charges. Souvent les réunions sont privées. Les Frères qui sont inspirés apportent un message. Ce sont des réunions d’édification. Le recueillement silencieux joue un grand rôle dans le culte. Les cantiques chantés sont extraits du recueil : Choix d’hymnes et de cantiques spirituels de Vevey. L’ordre du culte n’est jamais fixé d’avance; il varie: prières, cantiques, silence, explications bibliques.

SACREMENTS : Les Darbystes en reconnaissent deux : le baptême et la Sainte-Cène que les frères peuvent administrer. La cène est réservée aux convertis. Elle est distribuée sous forme de pain et de verres de vin. Le baptême est fait par immersion après une profession de foi. L’âge minimum des baptistés est 13 ans.

ADEPTES : Ils viennent surtout des petites communautés protestantes séparées des Eglises officielles, ce sont surtout des paysans.

DIFFUSION: Angleterre, Irlande, Suisse, France, Nouvelle-Zélande, Etats-Unis, Australie, Guyane, Grèce, Egypte, Chine, Afrique du Nord, Indes, Japon, Italie, Espagne, Allemagne.

ARRIVÉE EN FRANCE : Les premiers missionnaires darbystes arrivent en France en 1843 ; les premiers adeptes sont recrutés dans l’Ardèche, le Gard, le Tarn, la Haute-Loire, la Drôme et le Rhône. Le Darbysme français est constitué officiellement en 1850, où Darby préside le Congrès d’Annonay.

JOURNAUX : Le Messager Evangélique, mensuel, 32 pages, parait à Vevey en Suisse depuis 1859; L’Appel, mensuel, édité à Tonneins en Lot-et-Garonne; Le Salut de Dieu, mensuel, édité à Valence, 24 pages ; La Bonne Nouvelle, pour les enfants, mensuel, 24 pages, édité à Vevey; Lettres sur l’œuvre du Seigneur, bulletin des missions.

BROCHURES : L’Assemblée de Dieu, édité à Vevey, déposé à Valence, 80 pages, paru en 1949 ; La Bonne Semence, un calendrier à effeuiller.

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES DANS LE MONDE : 300.000

NOMBRE D’ADEPTES EN FRANCE : 10.000.

CENTRE FRANÇAIS: 233bis, Faubourg Saint-Honoré, Paris.

LIEUX DE CULTE: 128 assemblées en France, les principales sont dans le Rhône, les Cévennes, l’Agenais, la Haute-Loire, l’Ardèche, surtout la vallée de l’Eyrieux, l’Isère, le Gard, l’Hérault, le Pays de Gex, surtout à : Besançon, Bordeaux, Dole, Marseille, Mulhouse, Nérac, Niort, Paris, Strasbourg (13, Rue de la Nuée- Bleue), Toulon; Chemin Chevalier à Lens.

Les DARBYSTES LARGES

NOM OFFICIEL: Eglise Evangélique des Frères.

AUTRES NOMS: Assemblée Evangélique, Frères larges, Assemblée Chrétienne.